Hoshang Merchant - The

Poetry of Jalwah*

Aparajita Roy

Sinha

Adapted from

Channel 6: Hyderabad & Secunderabad July 2003,

p. 22

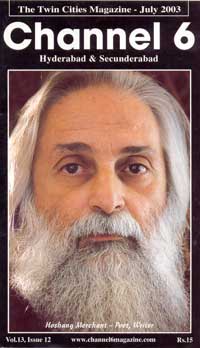

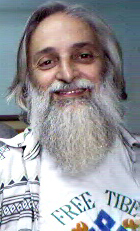

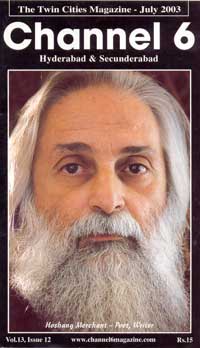

From Hoshang Merchant's mother's side he descends from

a line of teachers and preachers. He has a Masters from Los

Angeles and he did his dissertation on Anaïs Nin from

Purdue University, where he studied Renaissance and

Modernism. He has lived and taught in Heidelberg Jerusalem

and Iran where he was exposed to various radical movements

of the Left. His anthology Flower to Flame was

published by Rupa in '92. He is the editor of Yaraana:

Gay Writing from India (Penguin). I first met Hoshang

Merchant at a wedding dinner at painter Laxma Goud's house.

A few friends were sitting around relaxing over drinks,

while the long tables behind us were being arrayed with an

aromatic biryani dinner. Laxma is a Hyderabadi to the core

and that was one of my first experiences of the warmth of

the Telangana heart and hearth! -- liquor flowing, choice

food, and company (and conversation) to match. The

white-haired, bearded man in black sitting enigmatically

silent, glass in hand reminded me of artists I'd seen in

Bombay where I grew up: urbane, beautifully attired in

kurta, embroidered shawl and jooties. Only his eyes, alert

like a child's, darted here and there. This mix of

childlike candour and austerity is actually characteristic

of the poetry Hoshang writes. Hoshang is a poet-bard -- and

bards traditionally sang of truths that others did not know

or were afraid to speak. Children and holy men perform the

same service to society to this day.

From Hoshang Merchant's mother's side he descends from

a line of teachers and preachers. He has a Masters from Los

Angeles and he did his dissertation on Anaïs Nin from

Purdue University, where he studied Renaissance and

Modernism. He has lived and taught in Heidelberg Jerusalem

and Iran where he was exposed to various radical movements

of the Left. His anthology Flower to Flame was

published by Rupa in '92. He is the editor of Yaraana:

Gay Writing from India (Penguin). I first met Hoshang

Merchant at a wedding dinner at painter Laxma Goud's house.

A few friends were sitting around relaxing over drinks,

while the long tables behind us were being arrayed with an

aromatic biryani dinner. Laxma is a Hyderabadi to the core

and that was one of my first experiences of the warmth of

the Telangana heart and hearth! -- liquor flowing, choice

food, and company (and conversation) to match. The

white-haired, bearded man in black sitting enigmatically

silent, glass in hand reminded me of artists I'd seen in

Bombay where I grew up: urbane, beautifully attired in

kurta, embroidered shawl and jooties. Only his eyes, alert

like a child's, darted here and there. This mix of

childlike candour and austerity is actually characteristic

of the poetry Hoshang writes. Hoshang is a poet-bard -- and

bards traditionally sang of truths that others did not know

or were afraid to speak. Children and holy men perform the

same service to society to this day.

Laxma introduced me to

Hoshang as the daughter of a film-maker, and it broke the

ice at once. Over the years I have known him Hoshang has

surprised me again and again with his familiarity with the

film-world of Bombay, of the 50's and 60's. It is a world I

love and was intimately connected with. Many people have a

glamour struck, partly voyeuristic image of Bollywood, few

have the patience or imagination to see the tinsel behind

the glamour, the real struggles and heartbreaks underneath

the magnum opus tragedies. Hoshang's gaze is at the same

time both impassioned, and impartial, the poet's special

felicity. I do not find many people here who can talk with

the same sensitivity as Hoshang can about the films of my

father, and other directors of that time whom he admires

such as V. Shantaram, or Guru Dutt, and it drew me to him

at once. One day after he'd known me for some time, he came

for lunch and brought this poem as gift.

Remembering Bimal Roy

He worked silently

So that the birds could be recorded outdoors

It was the same indoors

So that the lightmen talked in whispers...

And if the labourer broke his life at the wheel

There was also the village girl dancing free

So that her voice melted in the mist

And you did not know if she was body or spirit

An entire generation of a new nation

Found itself drinking in this music

Not in order to forget, but just to be able to

breathe...

(The last line paraphrases

Dilip Kumar's timeless dialogue in the Bimal Roy

Devdas -- kaun kambakth hai jo bardashth karne ke

liye peeta hai - main to peeta hoon ki bas saans le

sakoon...)

In a few lines Hoshang

achieves a precise Japanese style impression of my father's

social concerns, the elemental human stories he told using

nature and music to give intensity to what could easily

have been just another boring document of suffering or

misery. I discovered that we shared not only love for Hindi

cinema but also a childhood in Bombay. He grew up on Pali

Hill where all the film stars had their homes (his bungalow

was opposite Sadhana's, next to Dilip Kumar and Pran) and

I, on Mount Mary Hill, a short crow's flight away. His

memories of his home on the hill by the sea call up

answering echoes -- I am not a poet or I too would have

written an ode to a yellow house near the sea, full of

high, old trees. The rhythms of his poem sketch a

delightful picture of the potent smells, surprises and high

points of childhood.

26, Pali Hill (circa

1992)

It was cooler

around the turn of the hill

where we smelt and felt the sea

And then we went down...

Past jackfruit banana chikoo guava

Gardenia canna laburnum hibiscus beds of laceflowers

Till crotons met us at a green door....

And so we moved up:

We had just outbid Nimmi

The Barsaat star....

(26 Pali Hill is now where

Sunil Dutt stays. It was re-numbered and became No. 58 in

the 70's.)

Somerset: 58, Pali

Hill

Not a tree left and a Rs 50

fine from the Nature society

A wall or a warren of flats

Where the sea was

Not a shard of light

Not a whiff of breath

bats in rafters

from the trees

Someone suggested that there

appears to be no attempt on Hoshang's part to "grapple with

realities around" him, only a "craving for the past and for

the future," Hoshang replied, "Down with reality! But the

preceding poem has a dark and graphic broodiness.

Hoshang's irrevocable pain

and loss is entangled with the memories of his mother being

dragged through the divorce courts of Bombay. Hoshang's

father married again, a mere girl, two years older than

Hoshang, dispossessing his four children. Childhood's end.

The darkening of light. When the walls of Bombay closed

round Hoshang he fled to America (the ultimate dream

merchant) with money from his mother, believing that the

liberal west was the place for his emerging gay identity

(nothing could be further from the truth) -- fled Bombay's

changing skyline, Bombay's coarsening materialism, a

breakdown mirrored by the spectacle of his father

abandoning his mother for another woman.

Snakes from Eden

in our garden

Bombay's dying?

Bombay's dead!

Hoshang's mother died soon

after, before he could return to India. A recurring guilt

haunts Hoshang's poems about her.

Mother

You fought and you gave

up

Doing naturally what came best to you - dying

as a lark at morning

rising forsakes its nest...

Now I forsake you

Sweet Mother, Forgive me

"Bombay was not the same

afterwards," comments Hoshang, and one does not know when

exactly paradise was lost -- when Mrs. Merchant and her

children were forced to leave the "green house built

athwart a hill." Or when Bombay revealed itself to him as

the crass and friendless city it has become today, where

all is trade, friendship, even love and sex, and everything

(starting with Bollywood of course) is in the grip of the

mafia. For Hoshang at least, his parents' divorce coloured

everything he ever did or thought -- even it must be said,

his sexual choices. "My effeminacy antagonised Father.

During their fights I stood square between mother and him.

Disturbed by my sign of maleness he aimed at my genitals."

The breakup seems to have left scars on all four children,

not least on an emotionally deprived, gentle woman-boy --

by his own admission, from the beginning, "mamma's boy". "I

was the only boy in school," he writes in his

autobiography. "Mother had decided I wouldn't swear or be

rough. I sang, danced, cooked and sewed. But I could not

thread needles... at home I dressed in a sari and sang and

danced under a cherry tree with my sister. My parents did

not like this." So much for childhood, for many of us the

defining patterns of our existences.

Hoshang Merchant has been teaching English at

Hyderabad University for fifteen years. In 1999 he was one

of the first academics to offer a course on Literature of

Sexual Dissidence to MA students as an elective. Hoshang

says the great influence in his life has been Anaïs Nin,

French poet and writer. He discovered her through her

Diaries, when his sister presented one of them to

him in America. Forever indebted to Anaïs Nin, it was her

courage and brutal honesty in writing about her love life

and sexual preferences which inspired him to become a

writer and write frankly about himself. He began a

correspondence with her that ended only when she died at

the age of 73 in Los Angeles in 1977. In Dharamshala,

studying Buddhist texts, Hoshang dreamt of her impending

death....

Hoshang Merchant has been teaching English at

Hyderabad University for fifteen years. In 1999 he was one

of the first academics to offer a course on Literature of

Sexual Dissidence to MA students as an elective. Hoshang

says the great influence in his life has been Anaïs Nin,

French poet and writer. He discovered her through her

Diaries, when his sister presented one of them to

him in America. Forever indebted to Anaïs Nin, it was her

courage and brutal honesty in writing about her love life

and sexual preferences which inspired him to become a

writer and write frankly about himself. He began a

correspondence with her that ended only when she died at

the age of 73 in Los Angeles in 1977. In Dharamshala,

studying Buddhist texts, Hoshang dreamt of her impending

death....

Hoshang is the first Indian

poet to have publicly acknowledged his gayness, or

homosexuality. In India, you are laughed at, abhorred, or

ignored if it is known or understood you are gay. Popular

Indian cinema is a good indicator of the general attitude.

But you are not crucified, as gays were in the universities

of the west when Hoshang went there. "India's Hindu culture

which is a shame culture rather than a guilt culture,

treats homosexual practice with secrecy but not with

malice." (But) Islam's strict strictures on any sex outside

heterosexual polygamous marriage and the strict segregation

of the sexes has spawned homophobic guilt and a vast

literature of homosexuality."

"My youth goes like this /

Green green glass bangles beside my bed / My blouse is on

fire / Who is to tell him, that Aulia Nizamuddin / You try

now, I've been trying all the time/ Time goes just like

this ..." "Bandish", by Amir Khusro

In India some people assume an innocence about the

existence of homosexual love that is at variance with

reality, for many Indian texts, including some ancient

ones, refer to the practice - termed the "literature of

male bonding," which Hoshang talks about in his

introduction to Yaraana, an anthology of

contemporary gay writing in India (Penguin, ed. Hoshang

Merchant). The east has always been more liberal than the

west -- there is a place for everything under the sun, as

Hindu philosophy claims. "India is divided fourteen times

into fourteen languages" bemoans Hoshang elsewhere.

Language and faiths jostle each other in India. Both akaar

and niraakar coexist, as do the carnal and the divine,

Shiva and Shakti, pirs and djinns, Buddha and Dalit and

Christ. If this seems ambivalence at its worst, and you

long for the clarity of black and white, then the eastern

experience -- and poets and their poetry, for that matter,

much of the artists' world -- is, I am afraid, not for you.

Hoshang is Parsi and he responds to all the varied cultures

that an immigrant community would absorb. The ancient

mythologies and richly textured wisdom of Hindustan

fascinate him, as does the stoic Christian faith. "I, a

male homosexual Parsi, Christian by education, Hindu by

culture, Sufi by persuasion...." is how he describes

himself. So you find a rich and wholesome potpourri of all

these influences in his poems -- this blurring of

identity/boundaries in someone like Hoshang, with his

Iranian past buried inside him (Iran being historically

poised on the meeting point of Muslim-Jew-Parsi-Christian)

is what makes his poetry so reflective of the juxtaposing

of opposites that I have described above. Add to that the

gender bend, the mix of female and male. The influence on

Hoshang of Sufism is endemic. The poetry of the Sufi

mystics which came to India via Arabia and other countries

of the Orient, holds God to be the only male. Therefore all

men must be female. And of course, all sufi poetry is love

poetry, God is the beloved, and the 'devotee' is always,

always, female.

Hoshang's poetry is simple

and direct (unlike his prose -- his work on Anaïs Nin is a

good example -- which is scholarly and full of political

and classical references). The Bellagio poems which await

publication are really a culmination of Hoshang's many

years as teacher and aesthete. "In the summer of 2001 I was

offered a writing fellowship at Bellagio. The luxury of the

villa, the breathtaking scenery, the service that tended to

spoil one, the food and wine were not conducive to work. At

the same time their impact on the sensitive mind coupled

with friendship with other sharp minds could not but be

great." The Little Theatre did a reading of the Bellagio

Blues in Hyderabad two months ago. Judging from the many

beautiful poems written by Hoshang while in Bellagio, the

scenery did have an impact. The following is my favourite.

Song like, it captures the place, the beauty, Hoshang's

sufi musings, and the pull of Christ in Italy with

"breathtaking" ease.

Memories of Bellagio

I sit on a rounded stone on

the pier

I hear the bells toll

The wind blow

The littlest pine-needle stir

All in unison

Who stirs the wind the pine the bell in unison?

I breath in and out: one with the pine, the bell, the

wind

Remember lake Galilee/where those who believed in the body

drowned!

Remember the fish and fisher on the lake

Hauling in a shoal of stars from lake-bottom....

Who am I? An old man on a

lake with a promontory behind him still to climb

I begin climbing: The bell, the wind, the pine-needle

keep me company

I am the gasping fish; I am the low glow of the

fire-worm

I am alive; I did not come here to die;

I halt for breath, for pause, for thought --

Who am I? Before this lake --

A shade, a shadow of a shade

A ripple on the water

A cloud upon a river

My own breath upon a mirror

Who will the boatman take?

I hear the cry of the mockingbird

I begin to climb the promontory.

Why do you write poetry,

Hoshang Merchant? Poetry is a way of confronting loss, of

breaking down walls, he answers. It's my freedom.

*Jalwah: Revelation, a sufi

term.

Home | Webmaster

From Hoshang Merchant's mother's side he descends from

a line of teachers and preachers. He has a Masters from Los

Angeles and he did his dissertation on Anaïs Nin from

Purdue University, where he studied Renaissance and

Modernism. He has lived and taught in Heidelberg Jerusalem

and Iran where he was exposed to various radical movements

of the Left. His anthology Flower to Flame was

published by Rupa in '92. He is the editor of Yaraana:

Gay Writing from India (Penguin). I first met Hoshang

Merchant at a wedding dinner at painter Laxma Goud's house.

A few friends were sitting around relaxing over drinks,

while the long tables behind us were being arrayed with an

aromatic biryani dinner. Laxma is a Hyderabadi to the core

and that was one of my first experiences of the warmth of

the Telangana heart and hearth! -- liquor flowing, choice

food, and company (and conversation) to match. The

white-haired, bearded man in black sitting enigmatically

silent, glass in hand reminded me of artists I'd seen in

Bombay where I grew up: urbane, beautifully attired in

kurta, embroidered shawl and jooties. Only his eyes, alert

like a child's, darted here and there. This mix of

childlike candour and austerity is actually characteristic

of the poetry Hoshang writes. Hoshang is a poet-bard -- and

bards traditionally sang of truths that others did not know

or were afraid to speak. Children and holy men perform the

same service to society to this day.

From Hoshang Merchant's mother's side he descends from

a line of teachers and preachers. He has a Masters from Los

Angeles and he did his dissertation on Anaïs Nin from

Purdue University, where he studied Renaissance and

Modernism. He has lived and taught in Heidelberg Jerusalem

and Iran where he was exposed to various radical movements

of the Left. His anthology Flower to Flame was

published by Rupa in '92. He is the editor of Yaraana:

Gay Writing from India (Penguin). I first met Hoshang

Merchant at a wedding dinner at painter Laxma Goud's house.

A few friends were sitting around relaxing over drinks,

while the long tables behind us were being arrayed with an

aromatic biryani dinner. Laxma is a Hyderabadi to the core

and that was one of my first experiences of the warmth of

the Telangana heart and hearth! -- liquor flowing, choice

food, and company (and conversation) to match. The

white-haired, bearded man in black sitting enigmatically

silent, glass in hand reminded me of artists I'd seen in

Bombay where I grew up: urbane, beautifully attired in

kurta, embroidered shawl and jooties. Only his eyes, alert

like a child's, darted here and there. This mix of

childlike candour and austerity is actually characteristic

of the poetry Hoshang writes. Hoshang is a poet-bard -- and

bards traditionally sang of truths that others did not know

or were afraid to speak. Children and holy men perform the

same service to society to this day.

Hoshang Merchant has been teaching English at

Hyderabad University for fifteen years. In 1999 he was one

of the first academics to offer a course on Literature of

Sexual Dissidence to MA students as an elective. Hoshang

says the great influence in his life has been Anaïs Nin,

French poet and writer. He discovered her through her

Diaries, when his sister presented one of them to

him in America. Forever indebted to Anaïs Nin, it was her

courage and brutal honesty in writing about her love life

and sexual preferences which inspired him to become a

writer and write frankly about himself. He began a

correspondence with her that ended only when she died at

the age of 73 in Los Angeles in 1977. In Dharamshala,

studying Buddhist texts, Hoshang dreamt of her impending

death....

Hoshang Merchant has been teaching English at

Hyderabad University for fifteen years. In 1999 he was one

of the first academics to offer a course on Literature of

Sexual Dissidence to MA students as an elective. Hoshang

says the great influence in his life has been Anaïs Nin,

French poet and writer. He discovered her through her

Diaries, when his sister presented one of them to

him in America. Forever indebted to Anaïs Nin, it was her

courage and brutal honesty in writing about her love life

and sexual preferences which inspired him to become a

writer and write frankly about himself. He began a

correspondence with her that ended only when she died at

the age of 73 in Los Angeles in 1977. In Dharamshala,

studying Buddhist texts, Hoshang dreamt of her impending

death....